The month of February is filled with many celebrations and events, however, all 28 days are notably commendable for Black History Month. The month is a platform for educating, celebrating, remembering, and honoring the African American community. With the current political movement that is Black Lives Matter (BLM), it is even more important to come together and educate yourself. If you are in a place of privilege, learn and listen to the stories being told.

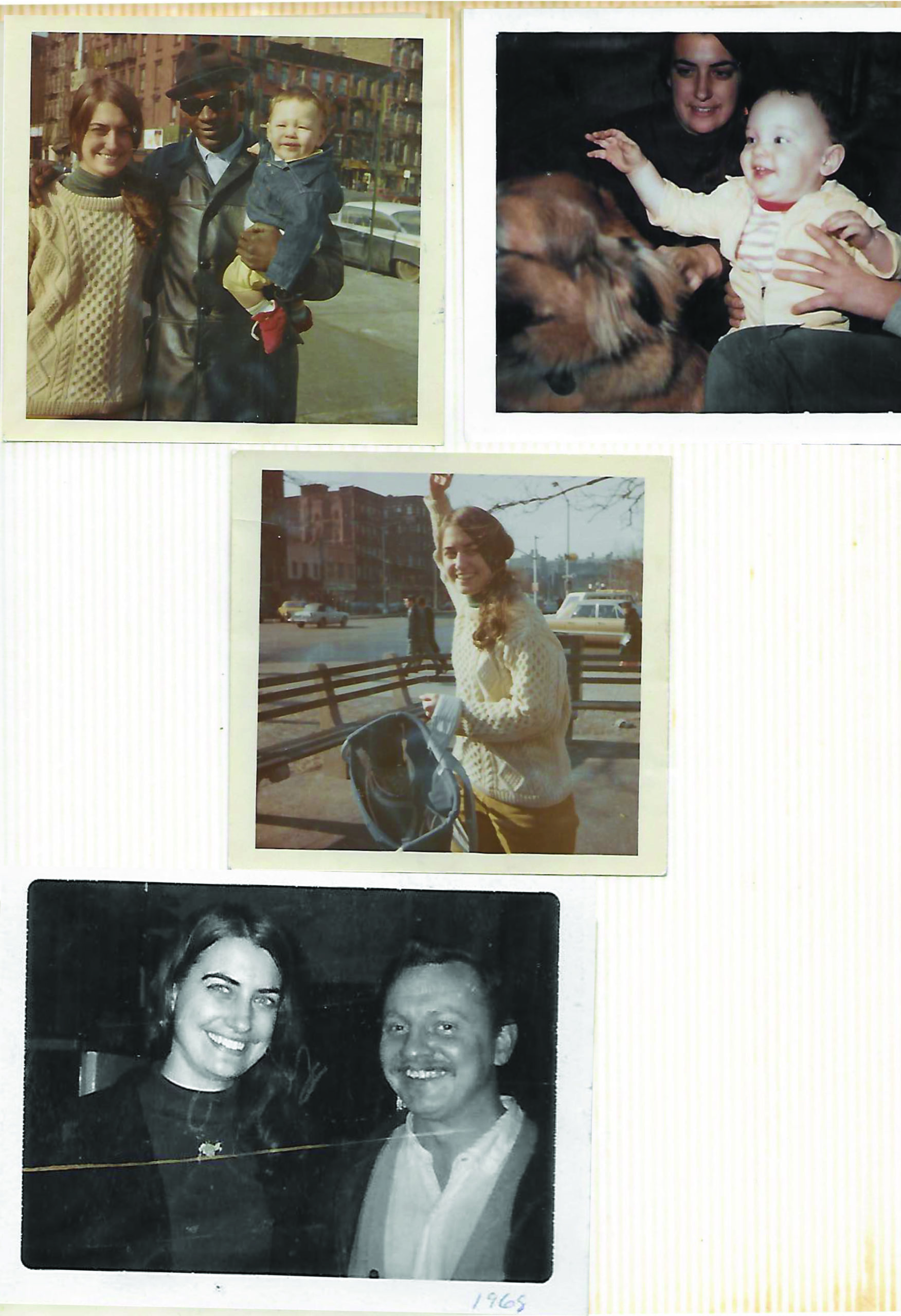

Nicole d’Entremont was 23 years old when she stepped foot in Selma, Alabama in 1965. d’Entremont was born in a small rural town outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She attended Rosary Hill College (now called Daemen College), a small private catholic girls school located in Buffalo, New York. With two classes left for her graduation, d’Entremont decided to leave school in 1964 to move to New York City (NYC). With the support of her family, she moved downstate to NYC to join the Catholic Workers Movement (CWM), where she worked for 10 years.

The Catholic Workers Movement was created by Dorthy Day:

a pacifist faith-based movement for social change that still exists today. They led from its beginnings in the Great Depression through the Vietnam War era. Day fed thousands of people, wrote newspaper columns, novels, and plays, and was arrested several times in protests.” (NPR)

“I have always loved an intergenerational classroom, a more unique way to learn and create, I knew what I wanted to do so I left college and moved to New York,” d’Entremont states with a shrug.

After some time d’Entremont went back to Hunter College to finish her degree, then 10 years after that attended the University of Southern Maine for her master’s degree in adult education. She continued to host intergenerational conversations, “I have always admired how much you can learn from others by just listening to people both older and younger than you.”

Within the CWM, d’Entremont was able to help out “the bowery, or skid row we called it, it’s 3rd Ave in NYC, very culturally diverse it boarded the Italian neighborhood and Chinatown. It was filled with flophouses and soup kitchens.” She explains how this way of educating herself by helping out her community was so useful in how she was able to gain knowledge outside of the classroom and get involved with the Civil Rights Movement.

When d’Entremont was a student at Rosary Hill, she attended a newspaper convention in 1962 at the University of Wisconsin. “I was meeting other students who were from the south and involved with the early lunch counter-demonstrations and the voting movements.” She recalls that the majority of the students were Black men, and spoke very openly about their experiences with the Civil Rights Movement.

d’Entremont explained how these interactions and the general knowledge she had on the freedom riders that were occurring made it even more enticing to be involved with the Civil Rights Movement. Since moving to NYC, she was even more connected to the life of poverty, seeing the lack of education in various neighborhoods, and was learning more about oppression. As a white woman involved with CWM, she wanted to use her voice to help out as much as she could.

“It was a natural evolution, I was already aware of these injustices, but after meeting those people in Wisconsin I just kept getting more involved,” d’Entremont states.

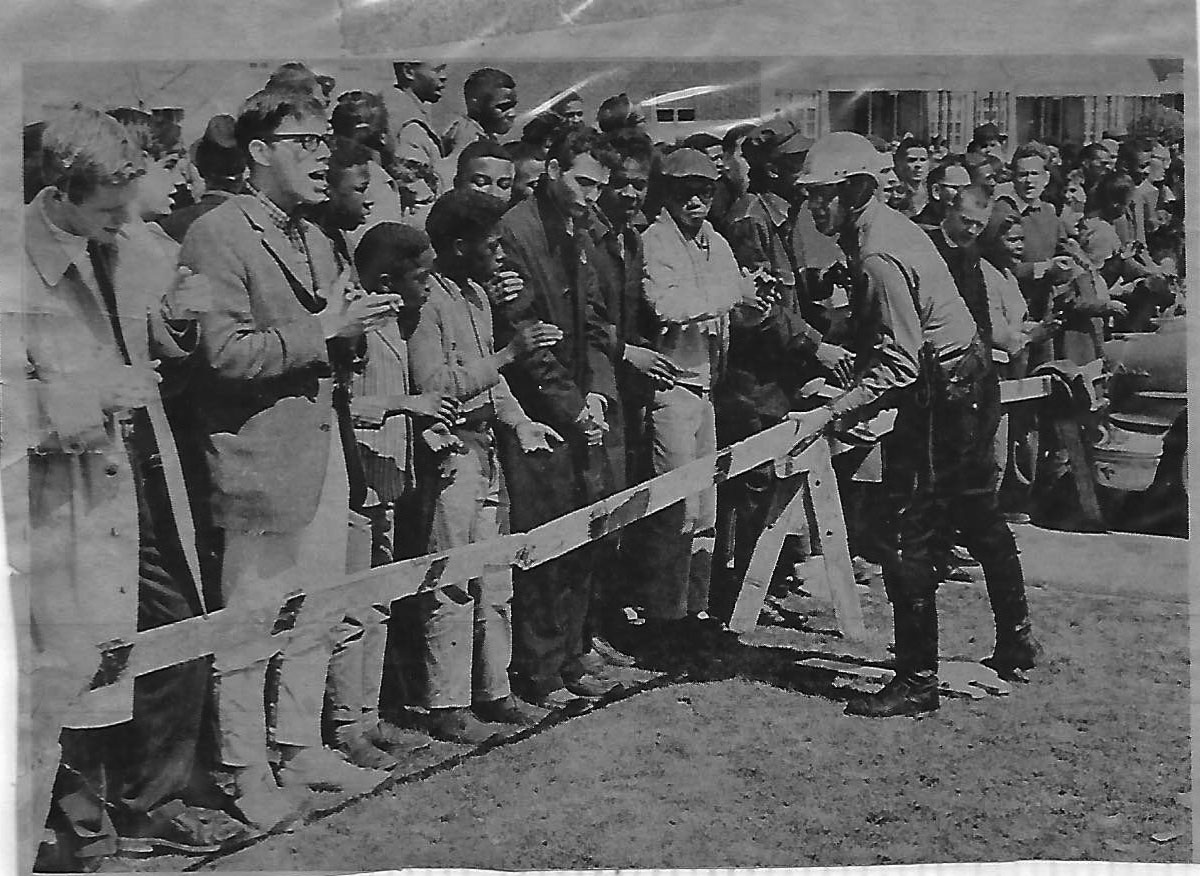

After about a year of work at CWM, d’Entremont wanted to travel to participate in the Selma marches happening in Alabama. The Selma Marches were a week-long event that happened between the dates of March 7 to March 21 in 1965. “The Selma Marches were a series of three marches that took place in 1965 between Selma and Montgomery, Alabama. These marches were organized to protest the blocking of black Americans’ right to vote by the systematic racist structure of the Jim Crow South.” (Archives.gov)

These marches covered 54 miles between Selma and Montgomery and because of these events the “Voting Act of 1965” went to Congress. However these events were not peaceful, many people were harmed by the police or the white population in Alabama and even members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). One notorious event was Bloody Sunday and can be considered the turning point of the Selma Marches. Bloody Sunday was the first real broadcast of police brutality on the American people. Once people crossed the bridge from Selma into where policemen used fire hoses, dogs, tear gas, and physical violence on the peaceful protesters and marches. These images were shown on television and over 50 million American viewers saw this around 9:30 pm on Sunday, March 7. (History.com) d’Entremont’s decision to go down to Selma was after Bloody Sunday, she went with a fellow member of CWM, Sean Calloway.

“Selma was a big turning point for me, it affected me deeply,” d’Entremont says as she remembers her time in Alabama.

During these three weeks, d’Entremont and others lived in the black communities and houses, as the members of the neighborhoods hosted the protesters, “It was called the Washington Carver Homes Projects, and it was next to Brown Chapel. The church was the meeting ground to get all the information about the next days and the events that were happening.”

She recalls them eating nothing but baloney sandwiches and Tropicana juice boxes. “All I can say is that it was such a welcoming place to be, the black community was so kind to us.”

d’Entremont describes her time in the March as:

A wonderful experience, a moveable feast of walking and music, and pretty thunderous when we reached Montgomery. And Martin Luther King’s speech and his arc of the moral universe bending towards freedom can still give me chills but beyond all of that was my feeling for the ordinary people of Selma and their courage and my hunch is that that feeling is probably a big reason why Martin Luther King could say the words he said that day.

As d’Entremont reflects on her experience and recalls the small memories of the loud crowd of people that she was surrounded. She recalls the fears and joys of her time in Selma. A life-changing experience that shaped the way she was involved with the Civil Rights Movement and how she carried herself as a young 20-year-old. She said that “Every black person to shelter us, took a big risk in helping.” As well as, “It was a real comfort for me when older people were there if I was going to be arrested, I wanted to be with people who also got arrested, there right with me, that gave me more courage.” The courage to place yourself in a new environment where you barely knew anyone, a place that wasn’t safe and often didn’t want visitors.

“I remember feeling safer in a group that practiced nonviolence, the Black community was fearless and heroic and everyone was friends, which made it a tight group, plus they were embracing of white people who came down,” she said.

Although she was in groups, it doesn’t mean that d’Entremont didn’t face fears or trouble. She distinctly remembers the words of activist Stokley Carmicheal, he was the first to raise the call for “Black power” and started the grassroots project for Lowndes County. This county in Alabama was notorious for harming and killing Black people (NYT). “ I believe in that time 80% of the population was black and the rest white and only one person in the black community could vote,” d’Entremont said.

d’Entremont shares her own experience with Lowndes county:

The march had happened, Sean and I had a flatbed truck, and wanted to get back to housing before nightfall. We were with a large group of people. They told the women and children to lay down as we went through Lowndes County. As I was laying down, I looked at the children, their eyes were big and wide, filled with fear. While the men were standing up for safety. Someone later someone had died on the same road, it was very sobering.

In a place where it was courageous to stand up for the desire to request to have equal rights and the right to vote. d’Entremont and many others like her participated in a March that shaped America. However, the learning didn’t all come from the Marches, d’Entremont and Calloway stayed an extra week to help with various cleaning up and helping in the towns, churches, to give back to those in the community and thank them for their hospitality.

Before anything was planned d’Entremont and Calloway had time to explore, as two white people, they were able to go into the black communities, sadly it did not work the other way around:

Sean and I went for a walk, we were wandering around when we realized we were being trialed by a truck. It was following us, a bunch of white men. Slowly following us. We kept looking back and saying this doesn’t feel right. We didn’t pick up our speed as we didn’t know where we were, or what to do. So we just kept walking and figuring out what to do. As we walked, we saw that just up the road was a bunch of homes with tin roofs. A woman was in her garden watching, motioning us to come into her home. So we walked right in. As soon as we stepped foot in, the truck took off very fast and left.

Enter Annie Vickers, an older woman in her 60s or 70s:

She had beautiful dark skin, and these lovely lively eyes, and a very thick southern accent. As soon as we walked in she started to question us, ‘How did you get here? Do you know how to get back to the church? What are you doing out here?’ She then drew a map that would take us directly back to the church and also told us to come back for lunch tomorrow. So the next day came back, we used her map. We walked in and she told us to sit in her bedroom. She lived in a tin house where she had a bedroom with a large bed, and huge quilt, she had us sit as she finished cooking lunch. She had prepared the entire meal in this small kitchen and she had a square cast iron stove.

As d’Entremont reminisced on the time she had with Annie, “she is right up there with Martin Luther King Jr to me,” and:

I even remember the meal she cooked us, you have to remember that we were eating sandwiches and orange juice for weeks. She made us fried chicken, collard greens, black-eyed peas, cornbread, I hadn’t seen food like that in forever, we just sat there eating on the bed. For dessert, she made peach cobbler and coffee. I felt so safe there, hearing the rain on a tin roof, felt safe and comforting for a long time in three weeks. I felt happy.

Vickers told d’Entremont “oh you chillen’ are rocking the boat, answering the Macedonian call.” Meaning that the children started this movement, the high school students back in 1962 with the lunch counter sit-ins, and how it started with the youth. This line reminded d’Entremont of the current situation and the Black Lives Matter movement and how high school and college students are the future, fighting the same fight.

“When I started, it was clear to me that white people have to shut up for a while” d’Entremont states. Some advice that d’Entremont has for her younger self as she is about to enter a life-changing experience is:

Hang out with some black women, and they understand how to deal with these situations. I am glad for all the experiences I’ve had, but I was very naive about a lot of things. It’s always better to listen and listen carefully, and understand what you don’t like and do like, stop being belligerent, hearing them out, it’s a way to understand both sides.

When discussing BLM, d’Entremont states that since BLM hasn’t declared the leaders of the movement that it will just happen, and these leaders will emerge, but that everyone should lead by example. She explains that leaders in the 1960s like MLK, James Meredith, and John Lewis all did what they encouraged others to do.

d’Entremont shares the words and thoughts of activist Andrew Young, he said that after Bloody Sunday, many people wanted to get guns to have protection for the rest of the marches. She explains that he responded that the opposite side will always have bigger guns, and how it is better to be nonviolent.“Tactics, it’s always better to reinvestigate nonviolence, no use in leading sheep to the slaughterhouse.”

Even though almost 40 years later many are fighting this same fight for racial justice and equality, there are many leaders and stories of history to better understand the fight. The old can learn from the young, and the young can learn from their elders and their stories. This is an example of intergenerational storytelling and creating unity and a community of wealth in knowledge. This February, use your time to better educate yourself, learn about the Civil Rights movement, understand your privilege, and work locally to create change. Happy Black History Month.