By Alyson Peabody, News Editor

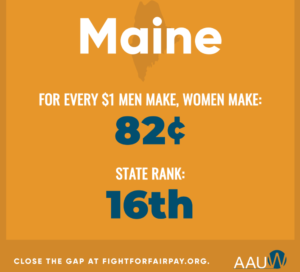

In 2019, gender pay equality is still a widely discussed topic. Last week USM hosted an event called “Exploring the Gender Pay Gap” with guest speaker Joan Fortin. Fortin delved into the extent of the gender wage gap, the long term economic ramifications and ways that women can advocate for higher pay. This conversation sparked interest in how this topic applies to women in Maine and at USM. According to data provided by Status of Women in the States, Maine women earn 83 cents for every dollar a man earns. At this rate, pay equality won’t exist in Maine until 2060.

Elizabeth Vella, a professor of psychology at USM, conducted a study during the 2013 and 2014 academic year to analyze if there were gender discrepancies in pay scale at USM. Vella was recruited by the former Lewiston Auburn College Dean, Joyce Gibson, to serve on a committee focused on recruiting and hiring women in the STEM field. She agreed to take on the task of looking at the public pay scale data available through the USM Office of Institutional Research to determine gender differences in pay among USM faculty.

Vella determined that controlling important predictors of salary, such as educational background, professional rank and years of service, would analyze the data most effectively. After controlling four different variables, gender predicted a $4,000 disparity in favor of men.

The first model included the number of years instructors taught at USM.

The second model included the years of service followed by rank, such as lecturer, assistant professor, associate professor and full-time professor.

“As you would assume, rank predicts pay, above and beyond years of service,” Vella said.

The third model included years of service, rank and college affiliation.

“The School of Law and Business boasts the highest salaries institution-wide. College affiliation for faculty salary matters,” Vella said.

She noted that when conducting research she withheld the salary of an assistant professor in the School of Business from all analyses due to salary earnings of $109,000 a year. This particular salary was greater than three standard deviations from the average pay scale for rank, representing an extreme outlier that would skew the data set.

The fourth model included years of service, rank, college affiliation and gender.

“While this is interesting,” Vella said, “what I found more compelling is my analysis of gender as a predictor of rank, which was a significant analysis. During that academic year, if we were to look at all the male full-time instructors at USM, 43 percent of them were at the rank of full professor. If you look at female full-time instructors, only 25 percent of us were at full professor rank.”

Vella stated that promotion to full professor is important to how much money professors can earn in their careers. She wanted to look at why there was a disparity at USM between gender and rank.

One thought Vella had is that there is a tendency for female professors to be tenured at the associate level before moving to the chair position for their department.

“Being department chair sounds prestigious, but in reality, chairs are the ‘caretakers’ of their departments who become preoccupied with administrative duties that then detract from publication record which prohibits full professor promotion, thereby locking female associate professor chairs into a mid-career pay bracket,” Vella said.

Vella advises USM to approach this problem by mentoring female assistant professors so that they can become astute negotiators, developing the skills needed to effectively navigate their own career trajectories.

“In my opinion, chairing a department ought to be a job for full professors, but I do concede that others at this institution may feel differently on this matter,” she said.

Fortin attributed the gender pay gap to a fault in a system that has existed for decades. The gap between male and female salaries does not exist at the extent that it did in the 1980s, but progress still needs to be done to ensure that a dollar for men equals a dollar for women regardless to factors like race, motherhood, or age, she said.

USM is not at fault for being one of many places still undergoing a gradual change, Fortin said. The university is open to discussing pay equity to understand why it exists and how USM can be a leader for positive change for equality.

“President Cummings believes in women in leadership. We are lucky to have a leader like him at USM,” said Ainsley Wallace, president and CEO of the USM Foundation.

Susan Feiner, a retired professor of economics and former director of Women and Gender Studies, agreed with the points made by both Fortin and Vella.

“The gender wage gap is not something one believes in,” Feiner said. “The gender wage gap exists. All economists agree that there is a wage gap. Professors of law and finance are paid almost twice as much as professors of social work and nursing. The question is: do the different work characteristics of a woman compared to men explain the difference in pay?”

Feiner provided statistics about gender pay equity from The Economist. Workers making more than $200k a year were approximately 90 percent male, $199k to $100k a year were 60 to 75 percent male, $99k to $50k were 50 percent male and 50 percent female. The lowest paid workers earning less than $50k are 90 percent female.

Feiner proposed four ways that workplaces can continue to close the gap.

“The federal office that is responsible for policing wage violations needs to be restarted and reopened,” she said. “Second, larger employers need to check that the already existing methods for scoring and evaluating jobs are not gender biased. Third, bosses should not be allowed to fire people who discuss salaries with their co-workers. Fourth, more workers unions. The gender wage gap in union jobs is half of what it is in the private sector.”

The consensus from Fortin, Vella, and Feiner is that women must network, advocate for themselves, and know when to negotiate for promotions that could lead to higher pay.

“If you’re going to negotiate, think about what you deserve,” Fortin said. “Do your homework and be prepared. Come up with a specific salary number and shoot high. It’s easier to work down than up.”

These skills can be accomplished by having mentors in the workplace to educate women on negotiation tactics. USM can re-evaluate the hiring and promotion process to make a change from inside the administration.

USM is a member of AAUW. Students interested in joining the AAUW, or wanting to learn more, can contact the Maine branches located in Bath-Brunswick, Caribou, Hancock County, Penobscot Valley and Waterville or visit aauw.org.