By Nex Staples – Staff Writer

Its walls ornamented with clean elegance, having made home to pieces of heart and antiquity since its founding by Margaret Jane Mussy Sweat in 1908, the Portland Museum of Art (PMA) is now temporarily housing two new exhibitions. These features highlight the works of men whose awe inspiring visions have made history: the creations of Walker Evans and Richard Estes. The pair of exhibits could scarcely be less alike, one’s spine bent from carrying the weight of an era and the other celebrating growth. However, it’s this contrast that allows for a crystal viewing of the universal theme of life that bleeds in each stroke or shadow of these pieces.

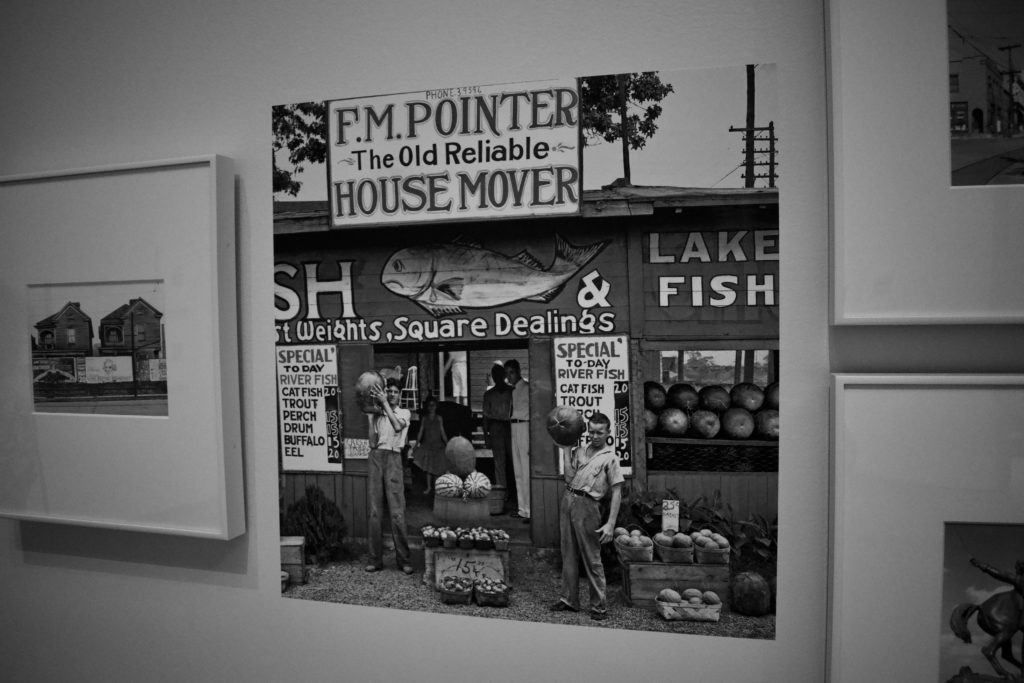

The downstairs exhibition, titled Walker Evans American Photographs, on view from Sep 10. to Dec. 5, displays work seeming to possess the ghosts of the tormented countenances and rotten walls of the Great Depression. Upon entering the room in which it’s displayed, it is easy for the newly struggling air to get caught in your lungs for a moment, caught off guard by the work. The four walls of the exhibit suddenly feel both more grand and smaller than a room should be, wide eyes becoming hungry for something to land on.

Almost every picture breathes feelings of sorrow and anguish, the misery stealing so much space that there’s room for little else. The overwhelming emotion quickly becomes partnered with that of emptiness and vacancy—almost like something is missing from the photograph. Almost like the something missing is life. The lack of color and the sharp, polished focus of the pictures creates deep ever present shadows around the subject of the work. The contrast is cold, as if the picture is trying to shut itself off from the viewer, yet the imagery of home—family houses, rocking chairs, old quilts—allows for the familiar warmth of humanity. The immortals living in the work are burdened by countenances full of upset, each looking with nearly unseeing, purple-rimmed eyes, with only one smiling face in the entire exhibit. The photographs show houses of worship and society falling, vacant of people and life—the pictures capturing heartbeats feeling more like obituaries, as if Evans knew back when he was behind the camera how important this time and these portraits would be.

Photographer Walker Evans (1903-1975) spent 50 years photographing the then modern yet ever-changing America—making a major impact on the documentary tradition. The tradition where one uses photographs as their voice, intended to show both the empyrean and wicked sides of society’s gray coin, as one of the style’s originators as stated by the Metropolitan Museum’s website. When a collection of his work was first displayed in the Modern Museum of Art in New York City (1938), Evans’s work became the very first one-person photography exhibit there. The PMA displaying many of those original pieces honors not only the fiftieth anniversary of the historical showing, but also the artist’s dedication to capturing the true and honest America of his time. His photographs, such as Alabama Tenant Farmer and Couple at Coney Island, New York, being known for the last handful of decades as being the purest form of representation the years had.

Upstairs on the third floor, Richard Estes: Urban Escapes on preview at the PMA from Aug. 20 through Nov. 28, exists in stark contrast to the photographs of Evans. Considered one of the founding photorealists, creators who use photos and photo bound techniques to produce a hyperrealistic end result, Estes (1932-present day) spent the beginning of his career working for others in graphic design before switching paths to his own painting practice in the 1960’s. His colors capture elaborate post war-age technology and cityscapes—Estes’ work standing out against others as they are the only well-known pieces of their kind. While many screen prints are copies of an already exhibiting image, Estes would combine multiple to make real the exact picture previously confined to his wonder-struck mind.

Estes’ exhibit displays the urban cityscapes and architecture that served as a substantial segment of his inspiration and amazement, emphasizing the significance of his creativity and unique style as well as the hopeful outlook of this era. The light of soul burns evident in the displayed works, the pieces often showing uninhabited lots that use the highlights of gleam and reflection, vibrant and bright colors contrasting now seemingly dim shadows to make the pieces exist as though they are brimming with life. They read as if hustling, tightly squeezed bodies previously wandered the confined square, yet were recently removed or are unable to be seen by the viewer’s eye, their energy sparking off of the canvas. This energy makes the pieces feel tight and far away yet also very intimate. Exuding electricity almost as though the painting is too grand for the frame.

The exhibit also features a wall titled “How to Screen Print like Richard Estes,” that walks viewers through the four main steps of the screen printing process, although the description warns and reminds readers that Estes worked under a different system, as well as two pieces centered in the room, shrouded by glass, each littered with hand-written notes and markups portraying the thoughts of the artist.

Working under the mission “art for all,” the Portland Museum of Art prides itself on representing diversity and history in a winsome, bewitching manner. If one wishes to view the above described exhibitions, the PMA on 7 Congress Square, Portland, Maine is free of charge for anyone under the age of 21, and costs 15 dollars for any student 22 or older. Elevators are accessible and face masks or coverings are required regardless of vaccination status.

Be First to Comment